The Guru and the Poet

_________________________________

In his room, Prabhupada reads from an advance copy of Teachings of Lord Chaitanya, which he has paid Dai Nippon Press to print. Prabhupada is very pleased.

“Now that they have done this nicely,” he says, “we can make immediate plans to print our Krishna book.”

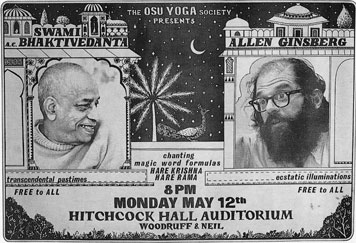

Kirtanananda and Pradyumna prepare prasadam for distribution tomorrow. New announcements are posted on campus: SWAMI BHAKTIVEDANTA AND ALLEN GINSBERG: A NIGHT OF KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS IN COLUMBUS. MAY 12. TRANSCENDENTAL PASTIMES. ECSTATIC ILLUMINATIONS.

Prabhupada talks about the financing of “the Krishna book,” which is to be a summary of the Tenth Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam, dealing specifically with the pastimes of Lord Krishna in Vrindaban and Mathura. George Harrison is particularly interested and has offered to donate printing expenses.

“Just see how these books are attracting,” Prabhupada says. “My Guru Maharaj always said that books are the big mridanga.“

At nine p.m., Allen Ginsberg enters. He has just flown in from Louisville, Kentucky. Concluding a long tour of college poetry readings, he is eager to return to his Cherry Valley farm in upstate New York. When he sees Prabhupada, he smiles broadly.

“Hare Krishna!” he says. As always, Allen touches Prabhupada’s feet, offering obeisances, then sits cross-legged on the floor. “So, we’ll sing tomorrow?”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says. “At noon today we had some meeting in the university. Kirtan. Wherever we go, there’s kirtan and speaking. You’ve seen our book, Teachings of Lord Chaitanya?” He hands Allen his advance copy. Allen handles it with respectful curiosity, first looking at the color paintings.

“ISKCON published? Printed where?”

“Japan,” Prabhupada says.

“Printed in Japan. Beautiful. Very industrious.” Then, grinning: “It’s marvelous!”

“The next book is coming,” Prabhupada says. “Nectar of Devotion.”

“What will that be? Your own writing?”

“No. An authorized translation of Rupa Goswami’s book Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu. Rupa Goswami was Lord Chaitanya’s principal disciple. He wrote immense literatures.”

Allen thumbs through the book, expressing interest in certain chapters. He admits that he’s not very familiar with the Chaitanya school. His India was one of impersonalists, Shivaites, hippy prophets, Buddhists.

“Do you remember a man named Richard Alpert?” he asks suddenly.

“No,” Prabhupada says.

“He used to work with Timothy Leary in Harvard,” Allen says. “Then he went to India and found a guru. Now he’s a devotee of Hanuman. We were talking about maya and the present condition of America, and he said that his guru told him that LSD was a Christ of the Kali-yuga for Westerners.”

“How is that?” Prabhupada asks.

“Well,” Allen goes on, “as Kali-yuga gets more intense and as attachment gets thicker and thicker, salvation has to become easier and easier.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says. “That is also the version of Srimad-Bhagavatam. But the process is kirtan, not LSD.”

“Well...” Allen says, hesitating. “Well, the reasoning is that for those who will only accept salvation in a purely material, chemical form, Krishna has the humor to emerge as a pill.”

The devotees’ eyes widen with concern. Prabhupada just smiles and shakes his head.

“If it’s material, “ he says, “where is your salvation? It is illusion.”

“The subjective LSD effect,” Allen says, “is to cut out attachment.”

“But if you’re attached to some material chemical,” Prabhupada counters, “how are you cutting attachment? If you accept help from matter, how are you free of it?”

Allen frowns reflectively, as if struggling to reconcile opposites.

“The subjective experience is that while intoxicated on LSD, you realize that it’s a material pill and that -- well, that it really doesn’t matter.“

Prabhupada again shakes his head. “That is risky,” he says. “Very risky.”

Still, Allen obviously would like somehow to convince Prabhupada of the value of the psychedelic movement, and perhaps receive a condoning nod. “So, if LSD is a material attachment,” he says, “which I think it is, then isn’t the Hare Krishna shabda also?”

“No,” Prabhupada says. “Shabda, or sound, is spiritual. Originally, sound produced the creation; therefore sound is originally spiritual. And from sound, sky developed; from sky, air developed; from air, fire developed; from fire, water, and from water, land.”

“So what was the first sound, traditionally?”

“The Vedas say Om,” Prabhupada says. “God and His sound are nondifferent, absolute. I may say, ‘Mr. Ginsberg,’ but this sound and you are a little different. But God is not different from His energy. Shakti, energy, and shakti-makta, the energetic, are nondifferent. Just like fire and heat. Fire can be differentiated from heat, but they are integral.”

“Then is the sound Krishna and Krishna Himself not different in all circumstances?”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says, “but it’s a question of my appreciation, realization, and purity. If we vibrate the sound Krishna, we immediately contact Krishna. Because Krishna is pure spirit, I immediately become spiritualized. If you touch electricity, you immediately become electrified. So, by vibrating Krishna, you become Krishnized, and when you’re fully Krishnized. you don’t return to this material existence. You remain with Krishna.”

“The impersonalists would say ‘merge,’” Allen says.

“That’s less intelligent, Prabhupada says flatly. “Merging does not mean losing individuality. When a green bird enters a green tree, he appears to be merging, but the bird has not lost his individuality. As Krishna tells Arjuna, we are all individual persons in the past, in the present, and in the future. Individuality is our nature and is never lost. Therefore our proposition, bhakti-marga, is to keep individuality and agree. Our surrender means we agree with Krishna in everything, although we are individuals. If Krishna says that we have to die, then we di -- out of love. So merging means merging in total agreement. That is the perfection of liberation: to retain our individuality and agree with God totally. We can come to this point immediately, or after many, many births.”

“And you believe literally in rebirth?” Allen asks.

“Yes. What is the difficulty?”

Prabhupada sits erect, looking frankly at Allen. There seems to be no difficulty at all.

“I just don’t remember having been born before,” Allen says.

“You might not remember your childhood,” Prabhupada says, “but that doesn’t mean you didn’t have one. Don’t you remember the time when you were a small boy?”

“Certain things.”

“Or do you remember when you were in your mother’s womb?”

“No.“

“Does that mean that you were not?”

“No.“

“Then your not remembering is not a reason for denial. The body changes, but I remain. We’ve changed bodies, but this doesn’t mean that we’re different persons.”

Again, Allen frowns, scratches his beard pensively. “It’s that I’ve never heard any reasonable or even thrilling descriptions of previous incarnations or births,” he complains. “I’ve never heard anything that’s actually made me stop and think, ‘Ah! That must be it!’”

“And why not? You’ve experienced that your body has developed from the size of a pea to this point. What’s so astonishing about changing this body and taking on another pea body?”

“What’s hard to understand,” Allen says, “is whether there’s any continuity of consciousness from one body to another.”

“If you don’t understand,” Prabhupada says, “you must consult some great authority. No?”

“No,” Allen says emphatically, shaking his head. “Not enough to make me dream of it at night. No. Not enough to make me love it. Words are not enough. Authority is not enough to make me love it.

Authority. From the very beginning, this has been the central point of contention. Before Prabhupada’s submission to Vedic authority, Allen is still the teenage rebel.

“You do not accept authority?” Prabhupada asks, seeming like a little boy incredulously asking another boy, “You don’t obey your mother?”

“Not enough to love,” Allen says, growing excited.

“No, apart from love,” Prabhupada says. “Consult. Consult.”

“It’s not that I don’t accept authority,” Allen says. “It’s just that I can’t even understand an authority that says that I’m there when I don’t feel myself there.”

“But if you’re in legal trouble, you consult a lawyer,” Prabhupada says, “and if you’re sick, you consult a doctor.”

“In America, we’ve had a great deal of trouble with authority,” Allen complains. “Here it is a special problem.”

“No, that’s misunderstanding. Authority must be accepted. A child accepts authority when he asks, ‘Mother, what is that?’ Asking is a way of acquiring knowledge. The Vedas tell us that if we want to understand the science of God, we must go to guru.”

“And do you understand your previous lives from the descriptions in authoritative texts, or from introspection?”

“We collaborate,” Prabhupada says. “Sadhu shastra guru vakya. We have to test everything from three physicians -- the sadhu, or holyman, the scriptures, and the guru. These three should not contradict but collaborate.”

“So what is the difference between the holyman and scripture?”

“None. We shouldn’t accept any man as a spiritual master or sadhu if he doesn’t agree with the statements of the scriptures. He should be rejected.”

There’s a long silence. Everyone waits for Allen to speak, but he only sighs in resignation. He’s just come to loggerheads with authority.

We discuss tomorrow night’s program. Allen tells Prabhupada that at poetry readings he has been chanting “Ragupati Raghava Raja Ram” and “Gopala, Gopala, Devakinandana, Gopala” to give the students a little variety.

“There’s no harm,” Prabhupada says, “but Hare Krishna must be chanted. Kirtan in the beginning and at the end, and in the middle you can discuss Krishna consciousness.”

“I think you’d better speak,” Allen says. “You’re more eloquent on the subject, and you might not like what I say.”

“So. tell about what you’re experiencing. And I will also speak. You have Krishna’s blessings upon you. You are not an ordinary man.

“I’m not certain that I’m worthy of that,” Allen says, laughing.

“That’s all right,” Prabhupada says, “but I know you’re not an ordinary man. Yat yat bibhutimat sattva.”

“Well, since the car crash, I’ve stopped smoking,” Allen says. “But I haven’t stopped eating meat.”

“Stay with us three months, Prabhupada says, “and you’ll forget all that. Just come with your associates to New Vrindaban, and we shall live together. You’ll forget maya and become fully Krishna conscious.”

“Well, we’ve a farm now in upstate New York, a vegetarian table, a cow and goats -- ”

“Economically, if a man has a cow and four acres of land, he has no problems,” Prabhupada says. “That’s the program we want to start in New Vrindaban. A cow and four acres. Then all the factories will close. There’s a proverb that agriculture is the noblest profession, is there not?”

“Yes.“

“And Krishna Himself was a cowherd boy. And according to the Vedas, a man’s wealth is estimated according to his grains and cows.

“Until the last century, at least, man has been living that way for twenty to thirty thousand years.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says. “Minimize bodily necessities. Just take enough to keep the body fit for Krishna consciousness. Plain living and high thinking.”

We decide to tune the harmoniums in the morning. I assure Allen that there will be sufficient microphones to prevent him from getting laryngitis.

Kirtanananda serves hot milk and plates of diced cantaloupe drizzled with honey.

“I’ve been learning to write music,” Allen tells Prabhupada. “My guru was a poet named William Blake. You know Blake?”

I’m surprised to hear Prabhupada say yes.

“He’s a lot like Kabir,” Allen says, encouraged. “I’ve been learning to meditate by singing poems by Blake, poems I’ve put to music.”

“I can give you many songs,” Prabhupada says, happy to Krishnaize everything.

Allen asks if he’d like to hear one of the Blake songs, and Prabhupada says yes. Pumping a steady, lively drone on his portable harmonium, Allen sings Blake’s “To Tizrah.” As he sings, Prabhupada looks like a delighted child being entertained, his eyes wide, his smile broad. Here, at least, in a kind of hodge-podge, hurdy-gurdy mantra-bhakti, there’s agreement. Allen is accepting the authority of Mr. Blake.

When Allen chants, “It is raised! A spiritual body!” Prabhupada says, “He believes in a spiritual body! That is nice. That is Krishna consciousness.”

“He apparently fits into what the West calls the Gnostic tradition, having bhakti ideas related to the Buddhist and Hindu traditions. Similar cosmology. Blake was my teacher.”

“He did not give much stress to this material body?” Prabhupada asks.

It suddenly occurs to me that Prabhupada thinks that Allen has personally met Blake. After all, “guru” usually implies this.

“Well, he didn’t toward the end of his life,” Allen says.

Allen then sings another Blake song, this time “The Chimney Sweeper.” I can sense that the devotees are fearing that Prabhupada is being offended by some mad poet. But Prabhupada smiles and claps his hands.

“And by came an angel who had a bright key,” Allen sings, “and he opened the coffins and set them all free...."

After this song, Purushottam announces that it’s five to eleven.

“Let everybody retire,” Allen says.

Prabhupada offers Allen two flower garlands strung around the photograph of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati. Allen accepts them, offers obeisances and bids farewell till the next day.

When Purushottam points out that Mr. Ginsberg represents certain “hippy values,” Prabhupada says, “Yes, that may be, but he is appreciating Hare Krishna, and on that point we agree. He is chanting Hare Krishna publicly, and if he goes on, then all these anarthas -- unwanted things -- will fall away. He will see them all as stool.”

In the morning, just after Prabhupada has finished a light fruit and milk breakfast, Allen returns. Prabhupada acknowledges his obeisances -- “Jai!” -- and immediately suggests that he write poems about Krishna. Then he mentions that one of the peculiar qualifications of a devotee is that of lunacy.

“The poet, the lover and the lunatic,” Prabhupada laughs. “The Krishna lover is also another kind of lunatic or poet, you see.”

“Except that writing of Krishna would mean concentrating all my consciousness on one single image of Krishna,” Allen says.

“Not image,” Prabhupada corrects.

“Well,” Allen smiles, “the one single thought, or name, or feeling, or awareness..."

“Yes, and to that end we’re engaging all these boys and girls in a variety of duties.” Prabhupada gestures to the devotees running about tending the Deities, cleaning, arranging, intent as bees. “For us, sleeping is a waste of time. The Goswamis used to sleep for only a half hour and were always engaged in Krishna consciousness. They have written thousands of books, and when they weren’t writing of Krishna, they were chanting or talking of Him, not allowing maya time to enter.”

“Who’s the most perfect Vaishnava poet?” Allen asks. “Mirabai?”

“In India she’s very popular,” Prabhupada says. “Most of her poems are written in Hindi. She was a devotee. She saw Jiva Goswami and wrote many poems.”

“Did she ever meet Lord Chaitanya?”

“No, but she appreciated the fact that He is Krishna. And her life was also exemplary. Her father gave her a small Krishna doll to play with, and in time she developed love of Krishna as her husband.”

“And Ananda Mayima? What is her position?”

“Impersonalist. She’s not a devotee. There are many impersonalists who take advantage of Vaishnavism, saying, ‘Chaitanya’s path, Shankara’s math.’ That is, follow the bhakti principle of Chaitanya, but ultimately accept the impersonalist conclusion of Shankara.”

“Which is -- ?”

“Shankara’s purpose was to defeat Buddhism, and to do so he preached an impersonalist philosophy, stressing Brahman. Buddha appeared in order to put an end to animal killing done in the name of Vedic ritual. In Srimad-Bhagavatam, he is accepted as the ninth incarnation of Krishna.”

“And the tenth?”

“Kalki.“

“And what is Kalki’s nature?”

“Kalki comes just like a prince in royal dress, on horseback, killing all rascals with a sword. No more preaching. Simply killing.”

Allen laughs, evidently pleased with the idea of a Hindu Second Coming.

“You may laugh,” Prabhupada says seriously, “but when Kalki comes, no one will have the brain to understand God.”

“No brain?”

“People will be so dull. After all, it requires a little brain power to understand. Only when you are fully joyful in bhakti-yoga and freed from all material hankering can you understand God. Understanding God isn’t such a cheap thing. Not understanding, people say that God is this or that. When Krishna Himself comes, they reject Him. They prefer to create their own God.”

“And when will Kalki come?” Allen asks, still pursuing an apocalypse.

“At the end of Kali-yuga. Then Satya-yuga begins.”

“Which is -- ?”

“Satvic means pious. People in Satya-yuga will be pious, truthful and long-lived.”

“And are those the people who remain, or who are created out of the destruction?”

“It will not be complete annihilation,” Prabhupada says. “The pious will remain. Paritranaya sadhunam vinasaya cha duskritam. The miscreants will be killed, and the few pious will remain.”

“Do you think of this in terms of a historical event that will occur in the lifetime of your disciples?”

“No. This will happen at least 400,000 years from now. By that time, my disciples will be with Krishna.”

“Jai!”

“And those who will not follow them,” Prabhupada adds, smiling, “will see the fun.”

And as Prabhupada laughs, I imagine Lord Kalki sweeping the world on a great white horse, severing heads as easily as a child stomps ants.

“Will people still be chanting Hare Krishna in 400,000 years?” Allen asks.

“No,” Prabhupada says. “Hare Krishna will be finished on this earth within ten thousand years.”

“So what will be left?”

“Nothing. There will be, ‘I’ll kill you and eat you,’ and, ‘You’ll kill me and eat me.’ In this way, we’ll have full facility for meat eating. There will be no milk, no grain, fruit or sugar. Still, Krishna is very kind.” Prabhupada shakes with laughter. “Yes, very kind. He gives full facility. ‘All right, why eat cows and calves? Eat your own sons.’ Yes, just like serpents, they’ll eat their own offspring. Like tigers. There will be no more preaching, no brain to understand preaching, no preacher. Civilization gone to the dogs, they say. And then Kalki will come and say, ‘All right, let Me kill you to save you.

“Do you also see this as an actual historical event? That is, Hare Krishna chanting will diminish in ten thousand years?”

“Oh yes, but now it will increase.”

“Until?”

“Ten thousand years, then diminish. People will take advantage of Hare Krishna for the next ten thousand years.”

“Then this is like the last rope,” Allen says, “the last gasp.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says. “The duration of Kali-yuga is 432,000 years, of which we’ve passed five thousand. There’s a balance of 427,000, and out of that, ten thousand is nothing.”

Allen shakes his head, as if bewildered by such cosmic calculations. In the Western tradition, long spans of time are considered uninteresting. The Second Coming is always just around the corner.

“But where is all this stated?” he asks.

“In the last canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam there are descriptions, Prabhupada says. “For instance, it’s said that in Kali-yuga, marriage will be performed simply by agreement. And people will think they’re beautiful just because they wear long hair. Also, it’s mentioned that the Germans will become kings and that the English and Mohammedans will occupy India. Many incarnations are also foretold, Lord Chaitanya and Lord Buddha being two.”

Then, to Allen’s surprise, Prabhupada points out that Lord Buddha engaged in “transcendental cheating” just to trick the atheists into worshipping God in the form of Buddha.

“Sometimes a father has to cheat his child,” Prabhupada says, “for the child’s own welfare. Especially if the child is insistent on some point.”

As Allen and Prabhupada converse, more devotees arrive from Buffalo and New York City. Devotees I’ve never seen before introduce themselves and offer to help. Kirtanananda puts them to work in the kitchen and sends them out to collect boxes to cart prasadam onto campus.

The more Allen and Prabhupada talk, the more it becomes obvious that there are questions that Allen wants cleared up before the campus meeting. I know how he feels. When he is with Prabhupada, his reservations about Krishna evaporate. But when he leaves that effulgent presence, the dark clouds of doubt return.

Again, Allen tries to clear away the clouds for good.

“It’s just difficult,” he says, “for me to conceive of vast numbers living a Hindu-language-and-food-based monastic life here in America. Now there are a number of Krishna temples firmly rooted, and I think they will continue” -- Allen’s expression is pained as he wrestles with words, trying to speak both truthfully and tactfully. “But I’m wondering about the future of a religion as technical as this, so complicated, requiring so much -- eh, sophistication in terms of diet, daily ritual, aratik, ekadasi and all that you’ve been teaching. Just how far can this spread by its very complexity?”

Complexity. Sophistication. When Allen first heard Prabhupada speak in New York, he used the word “esoteric.”

“First of all,” Prabhupada says, “you must understand that we’re trying to make people Krishna conscious. Therefore our program is to engage people twenty-four hours a day.”

“The orthodox Jews also have a very heavy, complicated, moment by moment ritual for that same purpose,” Allen says, “to keep them conscious of their religious nature. And that has maintained a small group of Jews over the centuries. But really, how far can total Krishna devotion, act by act, all day, spread? How many people can that encompass in a place like America? Or are you intending to get only a few devotees -- like several hundred or a thousand -- who would be solid and permanent?”

“Yes! That’s my aim.”

Allen looks startled. No one in America starts a religious movement without hopes of converting everybody. Prabhupada perceives his surprise.

“This is because Krishna consciousness is not possible for everyone,” he explains, almost apologetically, not wanting to offend Allen’s democratic notions. “In Bhagavad-gita we learn that after many births and deaths, the man of wisdom finally surrenders to Krishna. It’s not possible for a large body of people to grasp this. You see?”

Obviously, Allen would like Prabhupada to agree with his own democratic beliefs, but politically Prabhupada is a Vedic monarchist. The devotee-king should rule.

“Understanding Krishna is not a very easy thing,” Prabhupada continues. “Krishna says, ‘Out of many thousands among men, one may endeavor for perfection, and of those who have achieved perfection, hardly one knows Me in truth.’ So, Krishna consciousness is not easy because Krishna is the last word of the Absolute Truth. But Lord Chaitanya is so munificent that He has given us an easy process, this Hare Krishna chanting.”

“Then your plan here in America is to set up centers so that those who are concerned can pursue their studies and practise a ritual?”

“I personally have no ideal ambitions,” Prabhupada says. “But since life’s goal is to come to Krishna consciousness, there must be some society devoted to this end. It is not that we expect everyone to come. Our mission is to inform intelligent people that sense gratification is not the aim of life.”

“Now in America there’s a bankruptcy of sense satisfaction,” Allen says. “Everybody agrees.”

“There must be,” Prabhupada says.

“Our civilization has come to the end of its possibilities materially,” Allen says, “and everybody understands that. It’s in the New York Times editorials as well as the ISKCON journals. There’s a population explosion, and everybody is looking for an alternative to material extension. Now, my question is this: Is the mode of life that you’re proposing adaptable to many, many people?”

“I’ve already said that it’s not for many, many people,” Prabhupada answers calmly, again leaving Allen with the democratic masses.

“But there is a thirst by many, many people for an alternative, he insists.

“If they’re actually thirsty, they can adopt this Krishna consciousness,” Prabhupada says simply. “What’s the difficulty?”

“There’s an aesthetic difficulty,” Allen says. “There should be some flower of the American language to communicate in.”

“Therefore we’re seeking your help,” Prabhupada says.

“Well, I haven’t found a way,” Allen admits. “I’m still chanting Hare Krishna.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada concludes. “That is also my view.”

As noon approaches, devotees crowd into the room until there is no sitting space left. They even crowd around the doors and windows, eager to catch some rare pearls from Prabhupada, or see the famous poet converted.

“At least I’ve come to America with this view,” Prabhupada continues, “now that America is on the summit of material civilization. Americans are not poverty stricken, but they are searching after something. Therefore I have come, saying, ‘Take this, and you’ll be happy.’ If America takes to Krishna consciousness, so will other countries, because America now leads. And exalted persons like you should especially try to understand. Even a child can chant Hare Krishna. What is the difficulty?”

“But there are difficulties,” Allen says, “for many people. Following the rituals in this temple, for instance.”

“All my students are following,” Prabhupada says, “and the movement is spreading.”

“But it requires an adaptation of Indian dress.”

“That is not very important."

“And Indian food.”

“It is not Indian food,” Prabhupada corrects. “We are eating fruits, grains, and vegetables. Do you mean to say that this is Indian food?”

“But -- ”Allen looks vainly to the devotees for understanding. “But -- the curries!”

“You may boil only,” Prabhupada suggests. “It’s not necessary to like our taste. You can cook vegetables and prepare fruits, grains and milk to your own taste. Of course, you cannot offer meat to Krishna. But apart from this, what is the difference?”

“Well,” Allen ponders, “the food is basically the same material.”

“Yes. Just the style may be different. We are not prohibiting. Just adjusting.”

Adjusting. Allen seems to mull this over as he looks at the clean-shaved devotees, so different from Ohio State fraternity boys and San Francisco hippies. Is it only a question of adjustment?

“There’s a limit as to how much the pronunciation of Krishna will spread, I think,” Allen ventures.

“No limit,” Prabhupada says. “You can pronounce the word any way you want.”

“Rather, there’s a limit until the word becomes as common in English as any other English word.”

“It’s already in the dictionary,” Prabhupada says. “What more do you want?”

“A large, single, unifying religious movement in America,” Allen says frankly.

“So, here is Krishna, the all-attractive,” Prabhupada says. “What do you want or expect from the Supreme, the all-unifying? Everything can be found in Krishna: opulence, beauty, wisdom, renunciation, strength. He is the unifying center of all.”

There is a long silence, and again the devotees look to Allen for some sign of surrender.

“Well, everything you say is beautiful,” Allen finally says. “But -- but I’m not even convinced!”

“No?!” Prabhupada is genuinely surprised. “Why not? You’re intelligent. You’re a recognized popular poet. I take it you’re intelligent. You’re chanting.”

“The chanting is almost a physical body movement,” Allen says, “rather than -- ”

“That may be,” Prabhupada interrupts, brushing all this aside, “but your intelligence is sufficient for understanding. This is not sentimentalism, nor bluffing, nor money-making business. You know that from the beginning I came single-handed and chanted. That’s all. I never asked anyone for money.”

“That was never in question,” Allen laughs. “What was in question was the universe.

“I’m just some newly come foreigner,” Prabhupada continues. “Who cares for me? You’re a popular American leader. If you recommend Hare Krishna, people will join.”

“Well, I’ve been chanting Hare Krishna on this continent beginning in Vancouver in July, 1963,” Allen says, “and I’m finding there’s a limitation to the people joining the chant. It’s strange and new to people here. As it becomes more familiar, it might spread more. Part of the limitation is due to a natural resentment or resistance. People want a prayer in their own tongue, their own language. I don’t know. For the same reason, an American Indian chant wouldn’t take hold, nor even a Latin chant. So, is it possible to find an American mantra?”

“Mantra cannot be manufactured,” Prabhupada says. “It is not American or Hindu. It is transcendental. Like omkara.”

“You think the very nature of the sound is transcendental?”

“Yes.”

“Om is an absolutely natural sound from the throat to the mouth,” Allen says, “and yet even Om sounds foreign to us. It’s hard to get people to chant Om. I tried in Chicago with both Om and Hare Krishna.”

“But there’s no alternative,” Prabhupada says, laughing.

“No. We haven’t been able to think of one yet,” Allen says. “Some people have suggested, ‘God, God, God,’ but that doesn’t have the right ring.”

“Who’s going to chant that five minutes?” Kirtanananda asks.

“Well, you could almost do ‘Amen, amen,’” Allen says.

“That’s not English.”

“No, but it’s known in English. And maybe Krishna could become as well known as God or Amen.”

We look up Krishna in the dictionary and find that He is next to Kris Kringle.

“He’s next to Santa Claus,” Allen says.

“Yes,” Prabhupada notes with satisfaction. “Yes. Krishna is the center of all, the father of everyone. Not only human beings, but plants and animals as well. Sarva yonisu kaunteya murtayah sambhavanti.”

“But what do you do when different religious groups claim to be the center?” Allen asks.

“We welcome all religions,” Prabhupada says. “We don’t decry any religion. Our point is love of Godhead. Krishna is love, all-attractive, and we want to be attracted by Krishna, just as iron is attracted to some magnetic force. That is the test of true religion -- how much have you enhanced your love of God? Call Him Krishna or something else. What you call Him doesn’t matter.”

“Then, do you think that the Hare Krishna mantra could serve as an intermediary mantra to link the religious tendencies both of Christian and Moslem religions?”

“Yes. Any religion. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu says that you don’t even have to chant the name of Krishna. He does say, ‘If you have no suitable name for God, here. Chant Hare Krishna!’”

In the temple room, bells suddenly announce noon aratik. Prabhupada looks about the crowded room. The devotees offer obeisances and begin leaving.

“Let’s tune the harmoniums,” I suggest.

“Yes, we have to work on the music boxes,” Allen says. “We have to start material preparations for the evening.”

“That is not material,” Prabhupada says, smiling. “Here we have nothing material.”

“Ah yes! Shabda preparations,” Allen corrects himself.

“Shabda is original and spiritual. Shabda Brahman. We have to understand that there is nothing material. Everything is spiritual. That must be our vision.”

“Jai!” Allen exclaims.

“Jai Sri Krishna!” Prabhupada says.

We offer Prabhupada obeisances, then take the harmoniums out on the porch for tuning.

I quickly see the error in scheduling the 750-seat Hitchcock Auditorium instead of the basketball court. The front doors are blocked, jammed with students crowding sidewalks and stairs. Inside, all seats are taken, but students squeeze into the clearing below stage and along the aisles and balconies -- all in violation of fire codes. They clap hands, shout, and wave incense sticks. Strawberry and frangipani.

It’s not a typical O.S.U. Yoga Society meeting. It’s a midwestern be-in, a gathering, a happening. It’s Haight-Ashbury two years later.

Ranadhir and Hrishikesh run in circles trying to distribute Bhagavad-gita. It’s too chaotic to try to post devotees at the doors. Instead, we press through the crowds to sell books.

“We’re number one! We’re number one!” the students begin chanting.

“Krishna’s number one,” Allen says as we climb onto the stage with the harmoniums.

The cheering gets louder as Allen begins regulating the microphones. “Hare Krishna! Testing!” I notice some of my freshmen in the front rows; I’ve assigned an optional 500-word theme based on the meeting. Students sit knee to knee in the aisles. Someone brings folding chairs to the side stage for faculty. Devotees arrange roses and buttercups from New Vrindaban around the dais.

“About two thousand made it in,” Pradyumna tells me. “They’ve closed off the doors now.”

Allen pumps out his familiar hurdy-gurdy harmonium drone. He sits on a mat on the floor, one microphone buried in the harmonium keyboard, another in his beard.

“Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare,” Allen chants, his voice loud and heavy, chanting the same tune he chanted two years ago in the Avalon Ballroom. But now he’s not chanting to drug-hazy hippies and Hell’s Angels. The healthy corn-fed faces of blond, blue-eyed midwesterners are chanting back.

By the time Prabhupada arrives, all the students are chanting. He enters from behind the stage, heralded by devotees carrying flowers and incense, clashing cymbals, pounding mridangas. As he walks up the platform and sits on the dais, Allen brings the chant to an end.

“Very good. Don’t stop. Go on with the kirtan,” Prabhupada says.

A devotee hands Prabhupada his cymbals, and Allen asks him to lead.

Prabhupada draws himself erect. Ching ching ching, the cymbals clash. His brow furrows in concentration as he chants “Vande Hum,” “Sri Krishna Chaitanya” and then Hare Krishna. His melody, slower and not as showy as Allen’s, is easier to follow. The students pick it up quickly.

Prabhupada stands and raises his hands, inviting the students also to stand and dance. The response is immediate. Students in the aisles are first to their feet, then students in the rows and balconies arise. There is little room for dancing; a spontaneous bounce catches hold instead. As Prabhupada bounces on the dais, the students bounce also. As he waves his arms, they wave theirs. He leads them as a maestro conducts an orchestra, until gradually the inherent spiritual rhythm of the mantra itself prevails. We can no longer hear Prabhupada -- just the chanting, the clapping, the pounding on chairs.

As in a dream, I see my students before me dancing and chanting in ecstasy. Sandra Hunsaker, nursing major, clapping, her eyes closed. Jeff Horner, in agriculture, chanting so loud I see blue veins pop in white skin. Pretty, buxom, fresh-scrubbed Marilyn Butler, swaying to Sanskrit rhythms.

Prabhupada throws marigolds from his garland. The students shout, “Here! Here!” and scramble for the gold prizes. Allen continues pumping the harmonium, his head wagging back and forth, sweating under the lights, the devotees pounding mridangas, the cymbals still heard over the chant, but loudest of all the young voices empowered by the mantra, not even knowing the meaning of the words.

Then somehow, as remarkably as it began, it all ends, and Prabhupada’s amplified voice echoes the praise of the gurus.

“The amazing fact is that everybody was able to get up and dance, leaping out of their skins almost, after sitting frozen,” Allen says, speaking quickly into the microphone. “When ancient rhythms are flowing through everybody’s body, then certainly we desire to dance and sing rather than sit frozen. But such is the nature of our conditioning in this Kali-yuga...."

Allen then draws an ecological picture of Kali-yuga -- part Vedic, part Ginsberg -- as an age of robots, doom and pollution. After a brief synopsis of the age of iron, he introduces Prabhupada.

“I have known Swami Bhaktivedanta for about three years,” he says, “since he settled in the Lower East Side, New York, which is my neighborhood. It seemed to me like a stroke of great intelligence for him to come, not as an uptown swami but as a real down-home street swami, and make it on the street in the Lower East Side, and also open a branch on Frederick Street in San Francisco, right in the center of the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood....

“It’s strange that such a far-out and ritualized Indian form should take root in the United States a little more naturally than the more Protestant Vedanta Society or the extremely rigorous Zen groups. I think partly it’s due to the magnanimity, or generosity, or the old-age charm, wisdom, cheerfulness of Swami Bhaktivedanta, his openness of heart, his willingness to come down into the street, and his sense of his own divinity and the divinity of others around him. It is Swamiji himself who has made it possible for the bhakti-yoga cult of India to be planted very firmly here in America.”

Allen then defers to Prabhupada to “explain his divine self.”

Now Prabhupada receives the students’ full attention. He seems to float on air, not sit on his dais. His robes glow radiant gold; his eyes close in meditation as he prays: “Om ajnana timirandhasya.... His voice, low and wavering, repeats the prayer that he chanted when he first began translating Bhagavad-gita: “I was born in the darkest ignorance, and my spiritual master opened my eyes with the torch of knowledge. I offer my respectful obeisances unto him.”

His eyes open, and he looks at the audience as if he’s just arrived from Vaikuntha.

“My dear boys and girls,” he says, “I thank you very much for coming here and participating in this sankirtan function, or, as it is called, sankirtan-yajna, sacrifice.”

The students lean forward, concentrating, straining to make out the meaning through the unfamiliar accent. Here is someone very unlike all their other teachers. Here, at last, is a master.

“In this Kali-yuga age,” Prabhupada continues, “as poet Ginsberg has explained to you, everything is very degraded from the spiritual point of view. And from the material viewpoint also, people are reduced in their duration of life, in their merciful tendencies, strength and stature.”

It is the same message as always, the same I heard him proclaim that first night in Matchless Gifts. Now it is spelled out even more clearly for the young fresh minds of mid-America.

“When we chant Hare Krishna,” he says, “our original consciousness, Krishna consciousness and its joyfulness, begins. When we come to the platform of pure, spiritual consciousness, we become joyful, brahmabhuta.”

This joy, he explains, begins when we develop our love of God.

“Chaitanya Mahaprabhu has given a nice example of love,” he says. “He’s playing the part of Radharani, the conjugal consort of Krishna. Our Krishna consciousness is not dry. You see the picture of Radha and Krishna. Krishna is a boy sixteen years old, and Radharani a young girl, a little younger than Krishna. They are enjoying.

The students look at the picture on the stage beside Prabhupada. Radharani clings to Krishna, who stands independent, legs crossed, holding His flute while a cow nuzzles at His feet.

“We should love God without cause, but we pray, ‘God, give us our daily bread. I have come to You for my bread.’ This is not love of God. This is love of bread.”

Instant laughter and applause. The students are sympathetic, and Prabhupada does not waste time with dry philosophy. He tells them quickly and frankly their spiritual state.

“This transmigration of the soul, these repeated births and deaths, is a diseased condition of the spirit soul. That you do not know.” There is urgency in his voice, as if shouting for everyone to flee a fire. “In our educational system, there is no department of knowledge teaching what the soul is, what is after death or what was before birth. There is no science. It is very lamentable. Education in the name of simply eating, sleeping, and mating is not education, not if my bodily conception continues. The Bhagavatam says, ‘Yasya atma buddhi kunape tridhatuke. Anyone who is thinking that this body of flesh and bones is self -- he is an ass.'"

Again there is appreciative applause and laughter. Prabhupada looks at the audience as if it is one large individual.

“And because they conceive this body to be the self, they don’t even have common reason. This bag of flesh, bone, blood, urine, stool and secretion -- can this be soul? Can this be self?”

Looking out at the students, I see Doug O’Connor, engineering major, staring intently at Prabhupada. Sitting beside him, dainty, prissy Miss Karen Burke takes notes quickly.

“Because you cannot see it, you are concluding that there is no soul. That is ignorance. There is soul, and this body has developed on that platform. That soul is migrating from one body to another, and this is called real, spiritual evolution, and that evolutionary process is going on through 8,400,000 species of life....

“So, don’t commit suicide. Take to chanting this Hare Krishna mantra, and all real knowledge will be revealed. It is practical. We are not charging anything. We are not bluffing you, saying, ‘I shall give you some secret mantra and charge you fifty dollars.’ No. It is open for everyone. Please take it.”

There is urgency in his message as Prabhupada now implores the young audience.

“That is our request. We are begging you -- don’t spoil your life. Please take this mantra and chant it wherever you like. There are no hard and fast rules you have to follow. Wherever and whenever you like, chant, and you’ll feel ecstasy.”

As in deference to being hosted by a university, Prabhupada mentions that we have volumes of books for understanding Krishna through philosophy.

“We are not dancing and chanting sentimentalists. We have background,” he says, hinting at the Vedic tradition. On the other hand, he quickly points out that we are not dry mental speculators.

“Don’t foolishly try to speculate to understand the unlimited,” he warns. “It is not possible. Just become meek and humble and try to receive the message from authorized sources. You don’t have to change your work or conditions. Just hear. Then a day will come when you will be able to conquer the Supreme Lord, who is unconquerable. God is great. Nobody can conquer Him. But if you simply follow this process and try to hear about God from authorized sources, then one day you will be able to conquer the Supreme Lord -- ” Prabhupada holds out his hand to the mesmerized audience. “ -- within your hand!”

A dramatic pause and pindrop silence. Prabhupada leans back on the dais. Once again he seems to be floating, so unattached he is from materials, the paramhansa floating on the waters of the world, untouched by mundane desires, filled with love for Krishna.

“As Brahma-samhita confirms, you cannot find God by merely reading and speculating on Shastra, scripture. You have to conquer Him by your love. He’ll reveal Himself to you if you sincerely chant this Hare Krishna mantra. It will cleanse your heart, and then if you read just one chapter of Bhagavad-gita, you will gradually understand what is God, what you are, and what your relationship with God is. And when you understand all this and develop your love of God, then you will become perfectly happy.”

Finally, hands folded, Prabhupada concludes by paying reverence to the picture of Radha Krishna.

“This is our path -- Krishna consciousness,” he says. “The path of happiness. Hare Krishna.”

Applause. Prabhupada does not call for questions due to the audience’s size. Instead, he and Allen lead another chanting. The response is even more vigorous than before. Soon again, everyone is dancing, and Prabhupada stands on the dais and waves his arms, and the students shout and wave back.

A marvel. If approached on the street, these students respond, “I have my own religion, thank you,” and walk on. But now, inflated by Prabhupada’s presence, they chant with fervor, hungry for more spiritual food, their response outshining that of hip New York and San Francisco.

And after thirty minutes -- or an aeon? -- it all ends. Prabhupada chants the closing prayers, as we all bow down. Encircling the stage, the students press forward for a last look at Prabhupada.

Hands folded in blessing, Prabhupada walks quickly to the exit. He has had his say. The effect his words will have is up to Krishna.

Students are in and out of the temple all the next day. Prabhupada gives afternoon discourses in his room, informal explanations of the basic lessons of Bhagavad-gita: I am not this body but eternal spirit soul.

Some students express serious interest in the philosophy. In the afternoon, there is a fire sacrifice, and Prabhupada initiates Luke (Lokanath), Carlos (Chaitanya-das), and Sherry (Chintamani) and weds our Sanskrit scholar Pradyumna with Arundhuti.

May 14. In the bright spring morning, Allen comes by to bid Prabhupada farewell before leaving for New York. On entering, he notices Prabhupada’s Deities on the dresser and enquires about them.

“When I was seven years old, my father was worshipping Deities,” Prabhupada says. “So, wanting to imitate, I asked him to give me a Deity, and he gave me Radha Krishna.”

“And did you wash Them and play with Them?”

“Yes. Washed, changed dress, served Them.”

“And you still do so?”

“In India, yes. Now my disciples are here, and they are tending Them.”

Prabhupada looks at the Deities and smiles broadly, then laughs. Allen sees that he is reading Srimad-Bhagavatam, and Prabhupada obliges him by reciting some verses aloud, chanting the Sanskrit in meter.

“This is very beautiful prosody,” Allen comments. “Very complicated.“

“Difficult,” Prabhupada says. “They have a metric system whereby so many words should be first, so many second. You cannot deviate. And rules for analogy and metaphor. Nothing should be repeated twice. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu defeated a great scholar just on the basis of one mistake.”

Allen says that at last night’s poetry reading, he was telling the students to chant Hare Krishna for President Nixon when he comes for commencement in two weeks.

“There’s a lot of resentment against the President and government,” Allen says, “from young people who don’t like war. It’s dangerous to show real conflict, but all that energy wants to express itself. So I suggested that they greet him by chanting Hare Krishna.” “That’s a very good service,” Prabhupada says. “Nixon said that he wanted to meet some religious leaders, so one of my disciples wrote him, but he never replied.” Prabhupada shakes his head as if it were strange indeed that President Nixon didn’t reply.

“Well,” Allen consoles, “if in this typical university the students greet him by chanting Hare Krishna, he may well invite you.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada laughs, “actually I came here thinking that America is in need of something substantial. I’m doing my bit, and if the government or the people help, this movement can be pushed nicely. Otherwise, it will go on slowly, however Krishna desires.”

Allen gives obeisances. “Now I must leave,” he says. “Hare Krishna!”

When he bows to touch Prabhupada’s feet, Prabhupada smiles and says, “All right,” appreciatively.

“We’ll have to chant again this summer,” Allen suggests, “in New York City. Just let me know two weeks in advance, and I’ll come down from the farm.”

“Yes,” Prabhupada says. “Thank you.” Then, indicating the white and red roses fresh from the Radha Krishna Deities: “Give him that garland!”

A devotee places the garland around Allen, who bows again and, wishing us good luck at New Vrindaban, leaves for his plane.

In the afternoon, my students deliver their 500-word themes, and I’m happily surprised when I read them. Those who chose to cover the meeting wrote their best compositions of the year. Back at the temple, I read some of them to Prabhupada. He listens closely, occasionally breaking into a smile, and says, “Just see! Just see! They are appreciating.”

I have rarely seen Prabhupada so satisfied with an engagement or its reaction. As I read from the themes, Kirtanananda and other devotees listen with satisfaction.

“Just one thing,” Prabhupada says. “This Yoga Society.” He looks directly at me. “You must change the name to Bhakti-yoga Society.”

“Yes, Prabhupada,” I say, shamefully aware that he had mentioned this before.

“If you just say ‘yoga,'" he continues, “people will think we are sitting like pretzels to improve our sex life.”

We all laugh, and Kirtanananda points out that no one on campus knows what “bhakti” means.

“That doesn’t matter,” Prabhupada says. “Let them come to find out. That will make them curious. Now, Purushottam, will you get my harmonium?”

May 21. In the evening, Paramananda calls from New Vrindaban’s closest pay phone.

“Prabhupada’s coming out in the morning,” I tell him. “We’re driving out in the Lincoln. Important. Get Mr. Thompson’s permission to drive over his property.”

“All right,” Paramananda says grimly, “but I can tell you now that the powerwagon doesn’t sound right. It coughs a lot and then dies out. We carried the battery all the way to get charged and -- ”

“Get Ron to look at it,” I tell him. “And make sure the upstairs is ready for Prabhupada to move right in. Sparkling clean, and lots of flowers.“

Paramananda tries to explain more about the powerwagon. He should know that there are no alternatives.

“Just get it fixed,” I say. “Tomorrow is the biggest day in the history of New Vrindaban. Just think! The first holy dham in the Western world created by Sri Krishna’s pure devotee. This is a historic event. The demigods may even be there.”

“It rained the other day,” Paramananda says quietly. “You’ll never make it up that road. I’ll be sure to ask Thompson.”

May 22. A most auspicious day, a cool, clear morning, the sky a baby blue without a wisp of cloud or speck of pollution, the sun rising early and bright, the aromas of spring everywhere, the dandelions with their cotton puffballs, the bulging umbrellas of May apples, the tiny, lustrous violets....

The devotees have swept out our newly purchased 1959 Lincoln Continental, washed the upholstery, waxed the exterior, polished the chrome, cleaned the windows, and filled the tank. It will guzzle twenty-five gallons easily during the three-hour drive.

Prabhupada descends the stairs of the temple and gives the day a sweeping joyful look. Then he turns to Kirtanananda and asks for a scarf. The air is brisk and clean. The devotees offer obeisances -- Pradyumna, Vamandev, Nara-narayana, Ranandhir. Lokanath opens the door of the Continental.

Prabhupada stops to appraise the long, black limousine whose best days are long past.

“You have bought?” he asks me.

“Yes, Srila Prabhupada.”

“And how much was it costing?”

“Three hundred dollars,” I say.

“Achha!” he smiles and gets in front. Kirtanananda drives, and Purushottam and I sit in back. The other devotees quickly scramble for their cars, and follow us down Interstate 70 to West Virginia.

.

Hayagriva dasa (The Hare Krishna Explosion, Chapter 17)

.

.